Byer – Rola – Plessey – Sontron – Optronics – Editron – Acoustisearch

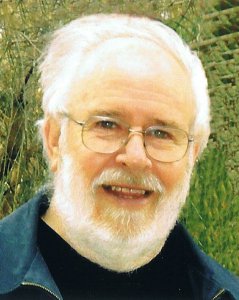

Graham Thirkell was an influential figure in professional audio engineering and manufacturing, and acoustic design in Australia. His innovative console and tape machine designs underpinned much of the recording industry in Melbourne and beyond, from the sixties through to the eighties, and his studio acoustic design skills saw his ideas realized in many major influential recording studios and broadcast plants right through to near the end of his life.

Graham’s father was a toolmaker, with a hobby interest in electronics, and Graham picked up these interests from him.

His early career saw him working at Byer Industries, the maker of the “broadcast standard” tape recorder of the time – the 77 Series.

Graham had a hand in many versions of the 77s. The original 77 (the 1956 Olympics Games machine), then the “Marks Brothers” – the Byer/Rola 77 Mark II and Mark III.

Bill Armstrong Studios, the Melbourne “hit factory” responsible for so many Australian hit records in the sixties, seventies and beyond were, for the most part totally reliant on equipment designed and built by Graham’s company Optronics (“Optro”). His equipment was also found in other recording studios, and television and radio stations throughout Australia.

The ABC was a big customer, particularly of his flagship Optro tape recorders – in full-track, stereo and multi-track configurations.

“Back in the day” of analogue audio and video recording, the tight synchronizing of audio from multiple multitrack recorders to video recorders and film dubbers was a critical necessity to allow greater creative freedom for film mixers, music recording engineers and producers. Graham’s Editron synchronizer solved the problem of locking together multiple machines, and developed quite a devoted user-base both locally and internationally.

His contributions to the film sound industry were recognised in 2007 with the Australian Screen Sound Guild awarding him its most prestigious award, the Syd Butterworth Lifetime Achievement Award.

Graham was also renowned as an acoustician, becoming first involved by collaborating with studio architect Peter Brown on the acoustic design of many music recording and radio studios in the mid seventies, including later work on Bill Armstrong’s Bank Street studios.

After Optronics and Editron, Graham concentrated on acoustic design and consultancy work through his company Acoustisearch.

With his thirst for knowledge, he was keen to take the field of room acoustics from an art to a science.

Graham had a hand in the acoustic design of over 100 studios around the country, often working with studio architect Peter Brown. His major projects included Radio Stations 3MP, 3XY, 2UW, EON-FM, 2MMM, ABC Southbank and many more. Music Studios included Armstrongs AAV/Metropolis, Flagstaff, Platinum, and Soundfirm at Fox Studios in Sydney, amongst others. His last major studio facility work was the HSV-7 Docklands studios.

Graham’s thirst for knowledge was insatiable.

Daughter Linda recalls that he was always excited about what was new. He was a voracious reader of books and magazines on the latest technology and regularly travelled overseas to attend trade shows and conferences to keep up with current developments in electronic design. More than one member of his family has remarked on the “metre-high stack of books and magazines” always by the side of his bed for late-night reading. Graham was always an eclectic reader on science and technology topics.

Katherine, his wife of 42 years recalled “Graham liked to share his excitement of a subject with pioneers and experts in the field; his creative and innovative approach to a subject helping to form firm and sometimes collaborative friendships with his often distant peers.”

Daughter Linda recalls that he surrounded himself with great engineers. Son-in-law Clem agrees, but adds that it was his ideas that stood out in this company. He was always talking to the customers, identifying the need and developing solutions. He was voracious in his appetite for knowledge. “It was amazing how innovative and creative that environment was” commented Clem.

Clem also comments that Graham could be in a meeting with people from a range of disciplines, and he could talk at their level to each of them. “He was usually the smartest person in the room.”

Son Gerrard wishes Graham to be remembered for his extraordinary ability to collaboratively pioneer, conceive and deliver (in most cases) world class ideas with a group of people with diverse disciplines. As a business entrepreneur it’s amazing that he was able to commercialize birthing the products he did, obviously his greatest strength was birthing dreams not so much nurturing them. He largely extended belief in other people’s abilities to pioneer with him, bringing out the best in them. Essentially he was a pioneering Father of technological dreams that blessed many.

Graham’s keen interest in the science of audio also led to his involvement with the Audio Engineering Society, and his becoming the first Chairman of the AES Melbourne Section, when it formed in 1974.

Graham’s unique approach to problem-solving served him well throughout his career.

Studio Architect Peter Brown defines Graham’s unique thinking with one amusing anecdote of the time when Graham and he were driving in San Francisco, travelling to George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch to meet with Tom Holman to discuss a project (Peter adds humbly “which of course we won!”).

Peter was driving and Graham was navigating, travelling across the Golden Gate Bridge heading to Marin County and Skywalker.

The exchange went something like this: “GT- ‘next turn you turn left … whatta ya doing ..’ PB- ‘I’m preparing to turn left ..’GT- ‘no it’s left ..’ PB- ‘yes it’s left!!’ GT- ‘no the other way!’ — it transpires that the only way Graham could deal with driving on the wrong side of the road was to switch his brain 180 degrees – so to him left had become right… his left & right were not the same as mine, Peter recalls. The journey was completed to the dialogue ‘turn left at the next turn – is that one of your lefts or mine – err, mine’ (PB then turns right)” . Peter also recalls that the subsequent discussion was completed in the car parked on a sidewalk in Sausalito (first turn left off the Golden Gate Bridge outbound).

An Illustrious Career:

Born on the 8th April 1937, Graham left school in 1951, aged 14, to take up an apprenticeship in electrical fitting and armature winding with Sun Electrics.

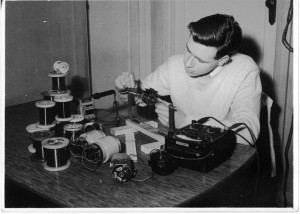

In 1952 he joined Byer Industries, and was involved with the groundbreaking 77 tape recorder.

In 1956, the same year that Byer Industries was delivering truckloads of 77s to the Olympics Host Broadcaster the ABC, for use at the Melbourne Games, Graham was awarded Apprentice of the Year – Electrical Fitting & Armature Winding. That must have been a busy and exciting year for him.

In order to address his lack of formal higher education Graham returned to night school for sub-intermediate and then Leaving Maths & Physics. He then went on to RMIT and achieved a Diploma in Electronic Engineering, all as a part-time student while working at Byer/Rola.

In late 1957 Rola Industries purchased Byer, and Graham progressed up to head the Research & Development (R&D) Department about the same time.

1961 saw Graham leave Rola Industries to work at Telefil, then a major recording facility in St Kilda. This was an era where much recording equipment was not available “off-the-shelf”, and Graham built much of their equipment at the time, as well as maintaining it all in top operating condition. It was at Telefil that he became close to their Studio Manager, Bill Armstrong – somebody who would feature strongly in his future.

After Telefil, Graham returned to Rola/Plessey as Head of Research & Development. Following the takeover of Rola by Plessey, the product range expanded to include broadcast cartridge machines and a new range of console tape recorders.

During his time at Rola/Plessey Graham was working out-of-hours in his own company Optronics, with the approval of his employers, manufacturing one-off and small-run professional audio products.

The Optronics company had been started in the mid fifties as a partnership with Graham’s astronomy buddy Barry Clark, to merge the Optics field and the Electronics field for a range of industrial applications. However, after a couple of years Barry amicably left the partnership to follow a public-service career in optics, leaving Graham as the sole proprietor.

It was a classic “cottage industry”. Parts and partially-built equipment filled all the empty spaces of his home, and the whole family was involved in manufacturing and assembly – with his wife Katherine looking after the business side and keeping the planning and finances on track.

There is a saying that behind every successful man there stands a woman… and that is undoubtedly true with Graham and Katherine. Katherine certainly held the company together over the years, allowing Graham to invent, design, and create.

Daughter Linda remembers winding transformers for pocket money during the school holidays among other tasks – musing that the skills learned at such times proved to be invaluable.

During his time at Rola, Graham also renewed his alliance with Bill Armstrong who was setting up his first Albert Road terrace house studio.

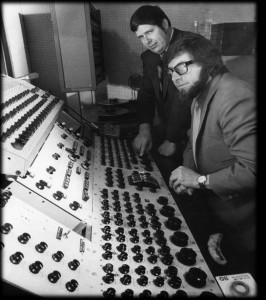

Bill relied heavily on Graham, and Optronics, to build specialist equipment like studio consoles, equalizers, compressors and the like – and to keep other equipment like multi-track tape machines running and on-spec.

This imported technology was often the only example of its type in the country, with nobody locally trained or qualified in its maintenance – and Graham often had to analyze its operation from first principles to identify how to repair it.

Graham also modified and improved much of the equipment at Armstrongs …

Armstrongs’ recording engineer Ernie Rose recalls that Graham was “probably the most intelligent person, the best user of information that I’ve ever worked with. He could digest a complex manual overnight and come back the next day and tell us how he could improve it. He had a capacity to be able to understand new technologies (and see ways to improve on it) which was outstanding”

By July 1969 Optronics had grown beyond what could be achieved working in his spare time in a back-yard shed, so Graham left Rola/Plessey to turn Optronics into a full-time concern.

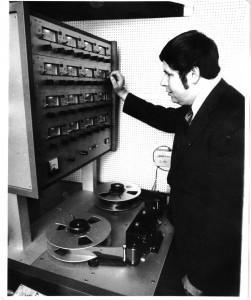

He moved the business into a factory building and started assembling the machinery necessary for the precision mechanical component manufacture that was going to be needed for his next project – studio tape recorders.

Here he received much advice and practical help from his machinist father, who contributed significantly to the mechanical excellence of the design.

Graham’s broad knowledge and skill-set was vital to this venture, with electronics, mechanicals, electromechanicals, and servo-systems design all being critical elements of the tape recorder design.

As in his days at Byer/Rola, almost all of the parts for Optro recorders were manufactured in-house to ensure rigid quality control.

He is quoted as having said that they “made everything except the heads”.

Mono, stereo and four-track versions of his Optro design were later purchased in significant numbers by the ABC.

The Optro machines were the first to incorporate a crystal-locked servo driven capstan motor, which resulted in significantly improved wow and flutter performance. It was an innovation later adopted by most other tape machine manufacturers. This advance also permitted the inclusion of an integrated varispeed function in the machines. Previously, synchronous capstan motors were used, which are speed-locked to the mains frequency. To vary the speed of such motors, a cumbersome (and expensive) external power amplifier and oscillator needed to be employed. Consequently until the Optro 1000 series (and its inevitable imitators) the varispeed function was not widely available to recording engineers and producers.

Bill Armstrong Studios – Albert Road.

In June 1971 the first Optro1000 16Track recorder was finally delivered to Bill Armstrong Studios.

This is claimed to be the first 16Track recorder used in Australia.

Bill Armstrong recalls that Graham was a perfectionist, and was always holding back his products’ delivery for that one last improvement or tweak – but that when delivered they worked superbly.

The “sixteen tracks across a two inch tape” format required a high level of tolerance in deck precision and stability, as well as tape handling. The excellent performance of these machines was a tribute to Graham’s electro-mechanical as well as electronic design and manufacturing skills.

Later a 24Track machine was designed and built and, naturally, Bill Armstrong’s studios again benefited from this ground-breaking initiative.

As well as the tape recorders, Graham and “Optro” continued to develop advanced audio consoles and outboard equipment – providing equipment to studios and broadcasters across Australia. A 1973 article in the media industry weekly B&T reports on the new 2SM Sydney studios and refers to Otpro mixing desks in their on-air studios.

In a newspaper article in 1971 profiling Graham in the wake of the new 16-track recorder installed at Armstrongs, Graham was quoted as saying (rather ruefully) that “certain aspects of most our work would be patentable at the moment – but a lot of people rely heavily on reading patents to get new ideas”.

This, together with the amount of money, attention, and time needed to lodge, and then defend patents, caused Graham to sometimes rely on what has been called the “Epoxy Patent” – where critical circuitry was kept secret by being potted in epoxy, and the circuit not published in the equipment schematic; to thwart “reverse engineering”.

He was not the only inventor to resort to such intellectual property protection, with it being a not uncommon practice in the ‘60s and ‘70s when audio and control mathematical functions were realized in hardware not software.

In 1974 the world started to change with the release of the first truly “personal” computer, the Altair 8800. It was a true hardcore electronics enthusiast’s device, sold as either a kit or fully assembled, and featured in the pages of the US “Popular Electronics” magazine.

Graham immediately saw the potential and purchased one and started to teach himself programming. He also saw the potential when the Apple II was launched in 1977, and soon had one of those as well, writing programs for acoustic design work on the Apple.

Acoustics:

Graham’s interest in acoustics had been wakened in the seventies, when he was involved in the construction and fitout of Bill Armstrong’s new Bank Street studios. Peter Brown was the studio architect, and with acoustics for music recording studios being such a fledgling and arcane discipline, Peter was having to “invent” solutions on-the-fly. Soon they were brainstorming issues and solutions.

This relatively unknown field fascinated Graham, who started actively researching variable acoustic solutions. Peter Brown commented that ”once GT got interested in something, that was it – he was like a dog with a bone”.

Graham pioneered the use of Time Delay Spectrometry – being the first in the country to employ a TEF™ Anaylser (Time-Energy-Frequency) for acoustic analysis and diagnostics.

He also championed the use of the quadratic residue (Schroeder™) diffuser.

Peter recalls that Graham did all the work for their signature Schroeder diffusers, and that he even developed a computer program for their design.

He also introduced Tube Traps to Australia, and for a period manufactured both Schroeder Diffusers and Tube Traps under licence in this country.

Graham became involved with the acoustic designs of Armstrongs’ later expansions and renovations, even collaborating with Kent Duncan on the Westlake enhancements to the Armstrong studios.

By the mid-seventies Graham was collaborating with Peter Brown on a range of other projects involving broadcast and major music studios.

Peter Brown recalls that they decided in the mid-80’s that they should do a world tour together to check out studios around the world to see how their work compared – and came back understanding that their work was in advance of anything they’d seen. Working in isolation in Australia they had come up with superior solutions to acoustic challenges, compared to the rest of the world.

In the late seventies Optronics was bought out by the David Syme company, the publishers of the Age newspaper and new owners of Bill Armstrong Studios.

At this time Optronics had sold the rights to the tape recorder design to IEM in the US, and Graham spent quite a bit of time over there involved in the technology transfer.

Before travelling, Graham and Katherine set up a computer store, The Byte Shop, selling IMSAI and other S100 bus computers and peripherals; which Katherine ran in his absence.

This highlights Graham’s fascination with computers, a trait that carried over to his son Gerrard, who began programming the computers from an early age. Gerrard’s software development skills would later became critical to the operation as the later Sontron/Editron products had such a significant software component.

The Editron came “into the mix” of Graham’s achievements in 1979, when renowned film mixer Roger Savage was mixing the first Mad Max film using multi-track tape and a rudimentary Ecco synchronizer. He enlisted Graham’s help in getting it all working effectively, but in typical style Graham immediately saw how it could be all done better.

As an aside, with this film Roger is widely credited with mixing the first major-release motion picture wholly on multi-track tape anywhere in the world – it was mixed at Armstrongs Studios in Melbourne, Australia.

With this experience, Graham refined his Editron design, which up to that point had been a simple device for synchronizing multiple videotape machines.

Using Roger’s input he turned it into an extraordinarily flexible multi-device synchronizer supporting all manner of audiotape, videotape, and sprocketed film devices. The key improvement on existing devices was syncing an audio machine using varispeed.

Roger recalls spending many hours with Graham, and his son Gerrard who was doing the software development, fine-tuning the Editron design, with Murray Robinson and Peter Cherny.

Before long Editrons were to be found in every local film mixing theatre. The Editron synchronizers were also exported, with several units sold to studios in the US.

Although it’s 1980’s technology, they are still highly regarded and in use in some facilities to this day.

In the late eighties, Graham suffered a major health setback, which required a long period of convalescence and rehabilitation.

It was a tribute to Graham’s resilience and mental strength that he recovered as well as he did.

After this experience Graham concentrated on acoustics work, establishing Acoustisearch to provide acoustic design services.

He continued to collaborate with Peter Brown on many studio acoustic designs.

Peter recalls that he and Graham had worked together on 100 to 150 rooms together – and Peter acknowledges that all of his later solo work was affected by Graham. Graham was the main driver at the development stage of the principles and techniques Peter Brown is still using to this day.

Graham, and Acoustisearch also became involved in several theatre and performance space projects.

He designed and built event-triggered digital sound stores and digitally controlled amplifiers for the Australian Bicentennial “First State 88” display at Darling Harbour in Sydney – and a special purpose film theatre in the display for John Wiley. He followed this up with several other projects with John Wiley culminating in the DTS Audio equipped Edge Theatre at Katoomba. This was the first large format (70mm) theatre in the world to use DTS audio, leading to the formation of the large format division of DTS.

Around the same time he built the digital playback equipment for The Stockmans Hall of Fame at Longreach.

His association with Tom Holman had seen him travel to the US and undergo the THX Certification Training allowing him to design and certify all aspects of the THX Theatre Audio Program.

In 2002 he carried out the THX design and certification for the ACMI Theatres at Federation Square. The ACMI Cinema was the only multi-format cinema, including large format, in the Southern Hemisphere at that time.

Graham designed, specified, and tested the acoustics and electronic facilities for the cinemas. The multi-format and multi-use nature of these cinemas made this a particularly challenging project.

The Other Side of Graham – Astronomy & The ASV

Fellow astronomer, friend and early business partner Barry Clark recalls “Graham had a lifelong interest in astronomy. At various times from his teenage years he was a member of the Astronomical Society of Victoria. In the late 1950s, he joined a small volunteer group interested in solar activity research and public outreach in astronomy. The group included Brian Devine and Barry Clark, and met on weekends at the South Equatorial Complex of Melbourne Observatory, which is between the Shrine, Government House and the Royal Botanic Gardens.”

The early fascination with astronomy never left Graham, but as so often happens life’s pressures often got in the way.

Nevertheless he accumulated an impressive array of telescopes and astronomical gadgets, including an 8inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain, and a 10inch Newtonian telescope.

Graham’s daughter Linda recalls many nights together with her father with the telescope in the back yard. Later she and husband Clem recall how they relished the visits to the family home when the skies were clear so the telescope could be swung into action for a skywatching session.

At one stage Graham even had an observatory constructed at the new house he was building at Berwick – Linda recalls helping him assemble the kit dome he imported for the observatory.

As usual, when Graham set out to do something, he did it right.

Graham died on 6th April 2010, and a brilliant audio mind was lost to us all.

As Issac Newton is quoted as saying:

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Graham was one of the giants who expanded the horizon for many who came after him.

Thanks are given to the multitude of family, friends, and former colleagues who gave so freely of their time to provide information and materials for this tribute, with a special thanks to Katherine Thirkell and Linda and Clem Berenger.

We would welcome contributions (or corrections) to this tribute from anyone who has first-person knowledge of Graham’s activities.

Anyone who has memories or experiences of Graham that they would like to contribute please contact the AES Melbourne Section on this link

Peter Smerdon

AES Melbourne Section.

12th January 2014.

Links to other pages:

The Rola Days 1 – Graham’s photos.

The Rola Days 2 – The Magnetic Drum products.